Understanding Python’s Method Resolution Order (MRO)

When working with Python, especially object-oriented programming (OOP), you’ll encounter inheritance and, at times, multiple inheritance. In such scenarios, Python provides a sophisticated way of determining which method to call using something called the Method Resolution Order (MRO).

If you’re diving into OOP in Python and wondering how the language decides which method to invoke when dealing with complex class hierarchies, you’re in the right place. Let’s break down how Python’s MRO works, why it matters, and how you can inspect and control it.

What is Method Resolution Order?

In Python, the MRO defines the sequence in which classes are searched when looking for a method or attribute. This becomes especially important in cases involving multiple inheritance. The MRO ensures that method lookups follow a consistent and logical path, preventing issues like calling the wrong method or skipping over a method altogether.

Python also provides a handy way to inspect the MRO of any class using the .mro() method, giving you a clear view of the order in which methods will be resolved.

C3 Linearization

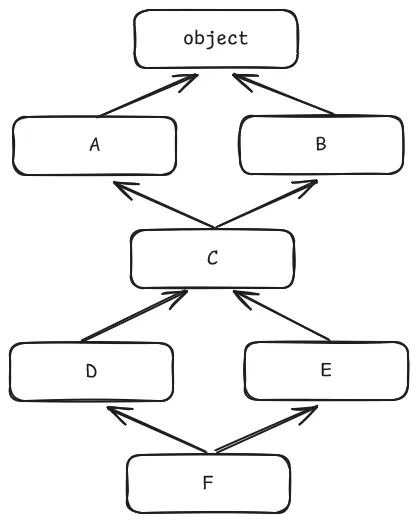

Since Python 2.3, the language uses the C3 linearization algorithm to compute the MRO for a class. In simple inheritance scenarios, this ordering can be intuitive, but as inheritance hierarchies grow complex, the MRO can become tricky to predict. Here’s an easy-to-understand example:

class A: pass

class B: pass

class C(A,B): pass

class D(C): pass

class E(C): pass

class F(D,E): pass

F.mro()

# [F, D, E, C, A, B, object]

In this example, Python uses the MRO to determine which class’s method should be called first. However, when the inheritance hierarchy becomes more complex, as in the next example, predicting the MRO by intuition is more difficult:

class A: pass

class B: pass

class C: pass

class D: pass

class E: pass

class F(C, A, B): pass

class G(A, D): pass

class H(B, D, E): pass

class I(F, G, H): pass

I.mro()

# [I, F, C, G, A, H, B, D, E, object]

To understand how this ordering is computed, let’s explore the C3 linearization algorithm.

C3 Linearization Algorithm

C3 linearization works by merging the MRO of parent classes in a way that ensures consistent order and avoids method conflicts. Here’s how the algorithm works:

Given a class C with base classes B1, B2, ..., BN, the MRO of C is computed as:

L[object] = [object]

L[C(B1, B2, ..., BN)] = [C] + merge(L[B1], L[B2], ..., L[BN], [B1, B2, ..., BN])

Where:

L[X]refers to the MRO of classX.- The

mergefunction takes the MROs of the parent classes and merges them, ensuring that no class appears before its superclass.

The steps in merging are as follows:

- Take the first element (head) of each list.

- Check the heads sequentially from left to right; a head is valid if it does not appear in the tail of any other list.

- If a valid head is found, select it as the next class in the MRO, remove it from all lists, and restart from the first head.

- If no valid head exists, Python raises an exception and refuses to create the class.

Now, let’s see how this works with the example I(F, G, H):

L[I] = [I] + merge(L[F], L[G], L[H], [F,G,H])

L[I] = [I] + merge([F,C,A,B,obj], [G,A,D,obj], [H,B,D,E,obj], [F,G,H])

# F is not in the tail of any other list, so it is selected.

L[I] = [I, F] + merge([C,A,B,obj], [G,A,D,obj], [H,B,D,E,obj], [G,H])

# C is not in the tail of any other list, so it is selected.

L[I] = [I, F, C] + merge([A,B,obj], [G,A,D,obj], [H,B,D,E,obj], [G,H])

# A is in the tail of [G,A,D,obj], so we move to the next head.

# G is not in the tail of any other list, so it is selected.

L[I] = [I, F, C, G] + merge([A,B,obj], [A,D,obj], [H,B,D,E,obj], [H])

# A is not in the tail of any other list, so it is selected.

L[I] = [I, F, C, G, A] + merge([B,obj], [D,obj], [H,B,D,E,obj], [H])

# B is in the tail of [H,B,D,E,obj], so we move to the next head.

# D is in the tail of [H,B,D,E,obj], so we move to the next head.

# H is not in the tail of any other list, so it is selected.

L[I] = [I, F, C, G, A, H] + merge([B,obj], [D,obj], [B,D,E,obj])

# B is not in the tail of any other list, so it is selected.

L[I] = [I, F, C, G, A, H, B] + merge([obj], [D,obj], [D,E,obj])

# obj is in the tail of [D,E,obj], so we move to the next head.

# D is not in the tail of any other list, so it is selected.

L[I] = [I, F, C, G, A, H, B, D] + merge([obj], [obj], [E,obj])

# obj is in the tail of [E,obj], so we move to the next head.

# E is not in the tail of any other list, so it is selected.

L[I] = [I, F, C, G, A, H, B, D, E] + merge([obj], [obj], [obj])

# obj is not in the tail of any other list, so it is selected.

L[I] = [I, F, C, G, A, H, B, D, E, obj]

Conclusion

The Method Resolution Order (MRO) is a crucial part of Python’s object-oriented system, ensuring that methods are resolved in a consistent, predictable way, even when multiple inheritance is involved. By understanding the C3 linearization algorithm, you can confidently navigate and control method lookups in complex class hierarchies.

I hope this guide has deepened your understanding of Python.

Keep calm and import this.